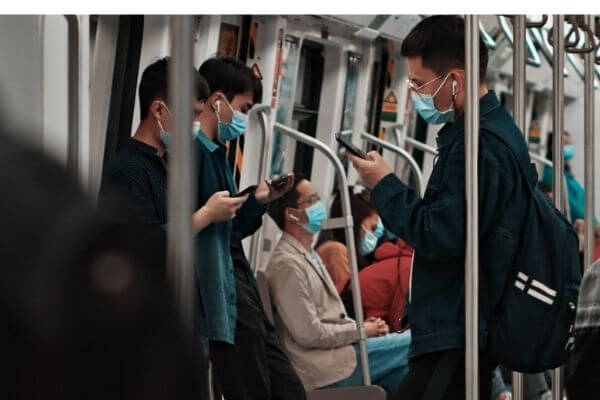

The E-justice in China is increasingly shaped by phones and other mobile smart devices as the main operating tools.

E-justice of Chinese courts has been frequently discussed in our earlier posts. It is referred to by China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) as ‘intelligent courts’ (智慧法院), and its typical example is the Internet Courts.

Driven by the COVID-19 Pandemic, China’s Internet court technology is spreading from three Internet courts to courts across the country.

During the past two years, intelligent courts are moving to mobile phones, allowing judges and parties to participate in certain aspects of litigation on mobile phones.

As introduced in an earlier post, parties living abroad can now file a lawsuit in a Chinese court on the Internet, by completing the relevant operations on the mobile online platform called “Mobile MiniCourt”.

Dr. Hu Changping, associate professor of the Law Institution of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, introduced this trend in his article “Judicial Practice and Limits of China Mobile Electronic Litigation: Taking ‘Mobile MiniCourt’ as an Example”. The article was published in “China Review of Administration of Justice” (中国应用法学) (No. 2, 2021). The journal is affiliated with the Institution of Applied Jurisprudence, a research institution under the SPC.

I. What is the “Mobile MiniCourt”

Mobile online litigation is a technology based on the increasing popularity of mobile phones and the continuous upgrading of WeChat applets and mobile litigation apps.

Courts in Ningbo, Guangzhou, and other Chinese cities have tried to integrate WeChat applets, mobile apps into intelligent courts, bringing the litigation from offline to online, and from the personal computer (PC) to mobile end.

The most effective one of them is the “Mobile MiniCourt”, which is gradually becoming a technical solution promoted by the SPC across the country.

The “Mobile MiniCourt” is a WeChat Applet, which is a web app service provided by China’s largest social media WeChat.

The parties may complete the operations of online litigation by the Applet on their Wechat APP.

The vast majority of Internet users in China have their own WeChat accounts. In November 2020, the number of active WeChat users has reached 1.2 billion, and thus the "Mobile MiniCourt" may reach as many parties as possible through the WeChat platform.

Not surprisingly, in the recent three years, the Mobile MiniCourt has gradually spread from cities such as Ningbo to courts across the country.

In March 2019, the Mobile MiniCourt was officially upgraded to the “China Mobile MiniCourt”, and pilot projects were conducted in 12 provincial regions in China. In January 2020, the SPC applied it to courts across the country.

II. Features of the Mobile MiniCourt

The author believes that the Mobile MiniCourt has the following features.

First, it is convenient.

The Mobile MiniCourt is installed on WeChat as one of its applets. Therefore, compared with the APP specially developed by the court, the Mobile MiniCourt is easier to obtain users.

In particular, parties and agents who do not use the mobile online litigation platform frequently are more willing to use the Mobile MiniCourt on their commonly used WeChat APP, instead of downloading another app.

Second, it has a wide scope of application.

The Mobile MiniCourt is not a completely new case system outside the existing intelligent court system. It is an entrance on WeChat based on the existing intelligent court system.

Third, it is of high operability.

The operation interface of the Mobile MiniCourt is simple and easy to operate. At the same time, the Mobile MiniCourt has powerful functions, introducing technologies such as face recognition, electronic signatures, and multi-access real-time audio and video interaction.

Fourth, it has extensible functions.

The Mobile MiniCourt adopts a modular design. Currently, it has six basic modules: case filing, service, evidence exchange, mediation, court hearing, and enforcement. The design of one function and one module greatly facilitates subsequent system upgrades.

III. The Limits of the Mobile MiniCourt

The Mobile MiniCourt currently has more than 30 functions including online case filing, case inquiries, online delivery, WeChat payment, mobile phone file checking, legal inquiry, court navigation, and enforcement application. By the end of 2020, the number of real-name users of China Mobile MiniCourt has reached 3,275,300, and courts across the country have used "Mobile MiniCourt" to handle more than 2.2 million cases. The total number of platform visits reached 522 million, and more than 2.14 million litigation participants experienced the Mobile MiniCourt.

However, the Mobile MiniCourt also has its shortcomings.

First, it applies to a limited group of litigation parties.

Although there are more than 900 million mobile Internet users in China, there are still a large number of elderly and poor people who cannot access smart devices. These people cannot use the services of the Mobile MiniCourt. Given this fact, the SPC also requires all courts to use mobile online litigation on the premise that all parties agree to apply.

Second, it applies to limited case types.

Not all cases are suitable to be tried online.

Online litigation is mainly appropriate for disputes about the Internet because most of the evidence in these cases is in electronic form.

However, as for traditional disputes, almost all evidence is in the form of paper evidence or oral evidence, which differ from the electronic evidence in a certain format and pixels in mobile online litigation, only resulting in increased costs and burdens on the parties.

Besides, cases that involve multiple parties, difficult case facts, or involve personal rights are also not appropriate to be submitted to mobile online litigation.

Third, it applies to limited litigation.

At present, China Mobile MiniCourt is used in a wide range of litigation stages, from case registration, documents services, conservatory measures, to online mediation, the examination of evidence, trial, and even to the enforcement, nearly covering all processes and stages of civil litigation. However, Chinese courts shall still take a cautious approach to those litigation stages of which the procedural rules are strict, and shall not blindly move the procedure online.

IV. Critiques of the author

The author states that the application scope of Mobile MiniCourt may be further expanded, and there is still room for growth. However, the author also indicates that while online litigation improves the efficiency of litigation, promotes judicial openness, and guarantees procedural justice, it also poses challenges to the protection of private rights, litigation rituals, and the principle of direct language. Therefore, Chinese courts should carefully pay attention to its limitations.

Contributors: Guodong Du 杜国栋 , Meng Yu 余萌